© Rabbi David Lapin, 2014

What the Midrash Means Series - 1:3

”Far be it from You to do something like this; to indiscriminately kill the righteous with the wicked… the judge of all the world will not do justice?…” (Bereishit 18:25). Rabbi Levi says: Avraham challenged Hashem:– If you want a world (olam) there cannot be justice; if it is justice you want, there cannot be a world. Why do You hold the rope at both its ends? You want to have both a world and justice! Give up one of them and if you don’t, the world cannot exist. –Bereishit Rabbah 39:6

Rabbi Levi turns Avraham’s rhetorical question, “will the judge of all the earth not Himself do justice?” into a statement of existential fact: it is impossible to be the judge of all the earth and at the same time carry out your standard of ideal justice. The world is not ideal and could not survive the application of absolute, ideal justice. This audacious challenge of Avraham to Hashem, which only appears in parshat Vayeira, the Midrash goes on to say, displays Avraham’s intense passion for righteousness and hatred of evil. This passion was responsible for Hashem addressing a human for the first time in the ten generations since Noach. He addresses Avraham in the opening phrase of our parsha. What is the meaning of Avraham’s arguement that justice and global survival are incompatible?

The word used for world is olam. Olam derives from the word he’eleim (invisibility). Hashem created a world in which His Shechinah and its sanctity is not obvious. He charges us with the mission of unlocking sanctity from within every particle of matter and every fabric of life in which it is invisibly hidden (he’eleim). However, Avraham argues, that by hiding His Shechinah so that we can unlock the energy of kedusha buried in a world in which He is invisible, we are deprived of the impelling force to do good that His blatant presence would have compelled in every creature. With this compulsion absent, the human condition can never be ideal and so it would be unfair for Hashem to judge us using His standards of ideal justice. It was His choice to hide Himself to create an olam, a world of invisible divinity, if He stands by this choice He needs to make allowances for human error.

The inherent tension between absolute justice or truth and the grayer area of human experience is a key to the understanding of Halacha. There is a dimension of Halacha that is absolute, rigid and unbending. This is Halacha in its ideal form represented by the written law, that which we call halacha de’oraaita. These ideal Torah stated laws are never-changing. Avraham however, introduces a new idea into the world. He recognized the need for an halachik process that interfaces between the absolutes of the Torah and the realities of human frailty. This interface is the ever-evolving laws of rabbinic tradition, or the halacha derabanan. Halacha derabanan is not less serious or less stringent than halacha de’oraaita, it merely utilizes different methodology and follows a different process of application. It is the halacha derabanan that keeps the Torah practical and relevant in every era. It is the halacha derabanan that makes the rigid, fundamentalist extremism of other religions a foreign concept to Judaism.

Halacha derabanan does not necessarily lighten the application of halacha de’oraaita, often, in recognition of human frailty it adds gezeirot (fences) to a halacha de’oraaita to help society avoid transgressing it. In other situations, although the ideal would be to carry out the halacha de’oraaita to the letter of the law, the reality of a situation makes that impossible, and there are times where, within the framework of halacha, specialist poskim (legal adjudicators) seek innovative approaches to apply the Torah’s law in ways that work. An example of this is the hetter iska (conversion of debt to equity with minimum guaranteed returns and capped upside), which allows creditors to be paid interest despite the Torah's prohibition, so as to keeps lines of credit open to people who might otherwise not be able to borrow. Or the peruzbul document which keeps credit lines open to businesses who depend on it, even through the shemitta year (Sabbatical cancellation of outstanding debt) which ideally cancels debt.

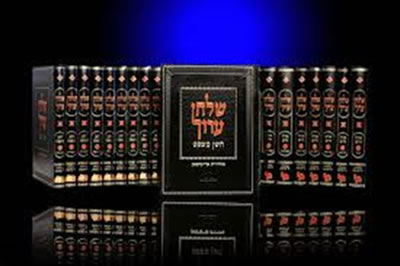

The Halacha that evolved over three thousand years was crystallized in the 16th century Shulchan Aruch. Still, Halacha continues to evolve until today in the form of the body of work known as she’eilot uteshuvot (rabbinic responsa). As new situations arise poskim (specialized legal adjudicators) apply the ideals of halacha to circumstances that are often far from ideal, and they do so in the way that is most faithful to the ideal.

This tight and delicate tension between ideal principle and real life remains the essence of halachik thought and method since Avraham first introduced it in his audacious challenge to G-d Himself. In our study and application of halacha today, it is important that we preserve this tension: It is important that we study a priori halacha in its ideal form, and only when we understand it in that form, explore the most effective way to practically apply it in a world that is less than ideal. The result, although not perfect, is whole. And in our world, wholeness is more valuable than perfection.